The Passion Pulpit by Donatello

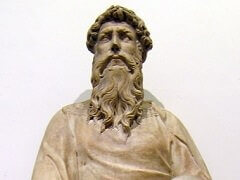

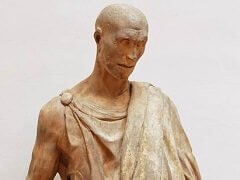

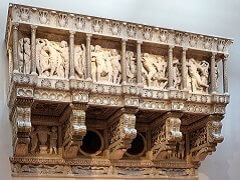

With the exception of a visit to Siena in 1457, where he produced a bronze Saint John for the cathedral, Donatello spent the remaining years of his life in Florence. His last work of importance was the bronze reliefs for the two pulpits of San Lorenzo, commissioned in c. 1460, and finished after his death by his pupil Bertoldo. The southern pulpit, now known as the Passion Pulpit, features images of Christ in Gethsemane, Christ before Caiaphas and Pilate, the Flagellation, as well as scenes of the Crucifixion, Deposition and Burial of Christ. These striking reliefs are noted for their expressionistic and violent depictions. Much uncertainty subsists regarding the origin of the two San Lorenzo pulpits (the other is the northern pulpit, known as the Resurrection Pulpit). Whether Cosimo d' Medici commissioned the pulpits remains disputed and it is now believed that the rather tall ornate red columns on which they are raised were a later addition from the sixteenth century.

There is no historical document concerning the original purpose or intended location of the two pulpits, which are the subject of much dispute in their present form. At an early date Baccio Bandinelli (1493-1560), a contemporary of Vasari, identified many faults in the relief work, which he attributed to Donatello's age and deteriorating eyesight. Bandinelli even went so far as to argue that the pulpits were the artist's worst work. Today, critics are less harsh and the San Lorenzo pulpits are celebrated for their intensity of emotion, as depicted in the numerous, tormented figures. There are no known models for Donatello's interpretation of these otherwise traditional biblical scenes.

Covered with reliefs concerning the passion of Christ, the pulpits are works of tremendous spiritual depth and complexity. In the Christ in Gethsemane relief, the disciples are portrayed at the foot of the Mount of Olives, overcome by their sleep, while Christ prays above. The sleepers and their varying contorted forms are positioned to give depth to the scene. The disciples to the right, just below Christ are proportioned smaller, while those further down, are larger in perspective. These lower figures separate the foreground from the landscape and even project out in front of the framing columns, adding further depth.

The Burial of Christ relief is bordered by two men standing on the right and left, before the framing columns, their forward position adding three-dimensionality. They serve as starting points for the semi-circular composition that meets the central motif. Proportions between individual figures are related to their spatial positions and the three-dimensional accentuation of the modelling is reduced correspondingly.

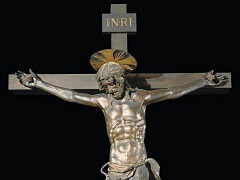

The dramatic scene of the Crucifixion, portrayed alongside the Deposition, depicts the suffering of the grieving women before the Cross. Few of the grim soldiers pay any attention to their sorrow, as they are more concerned with their duties. The tightly compressed group of figures contrasts with the scene above, showing the open space of the crosses bearing Christ and the two thieves, surrounded by angels. The earthly domain is presented as chaotic and wretched, while the Heavenly domain is open and free.

Little is known about Donatello's final days; he died in Florence on the 13 December 1466. We also know very little about his character and personality. The sculptor never married and he appears to have been a man of simple tastes. Patrons often found him difficult to deal with at a time when artists' working conditions were regulated by guild rules. He appears to have demanded a measure of artistic freedom, exceptional at the time. Though he associated with many prominent humanists, he was not a cultured intellectual himself; nevertheless, his humanist friends indicate that he was a connoisseur of ancient art. He possessed a more detailed and extensive knowledge of ancient sculpture than any other artist of his day, and much of his work was inspired by ancient visual examples, which he often developed into his own modern style. Although Donatello's supreme skill had been acknowledged by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, his name almost sank into oblivion during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and only in recent times has he been restored to the eminent position he deserves in thf history of art.